Anti-Majestic Cosmic Horseshit

My conflicted feelings about the Supernatural and the time I saw God

“You shouldn’t be afraid of ghosts. They’re very loving creatures. A ghost touched my honker when I was a young man.”

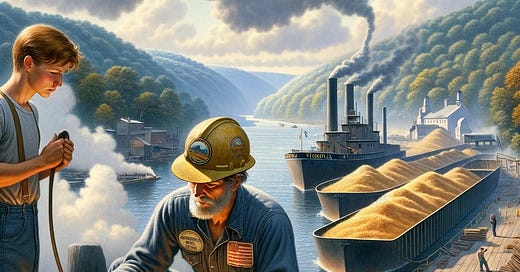

I was nineteen years old and working for a summer in the sawmill in my hometown when these words were spoken to me by a man named John Bell —I thought about using a pseudonym, but I doubt he would care, so just know there’s an actual guy in the world named John Bell who this part of the story is about.

Big John, as he was called, was a millwright and a West Virginian who spoke with a yodel. While every subsequent West Virginian I have met has insisted that this is “not a thing,” I can only assume that Big John hailed from an earlier and more cinematic version of the state now lost to self-conscious modernity. Apart from his yodeling manner of speech, he was known far and wide for having a “honker” roughly the size of a can of Pringles. Not that I ever saw it, but other men swore by it with envy, including my own father.

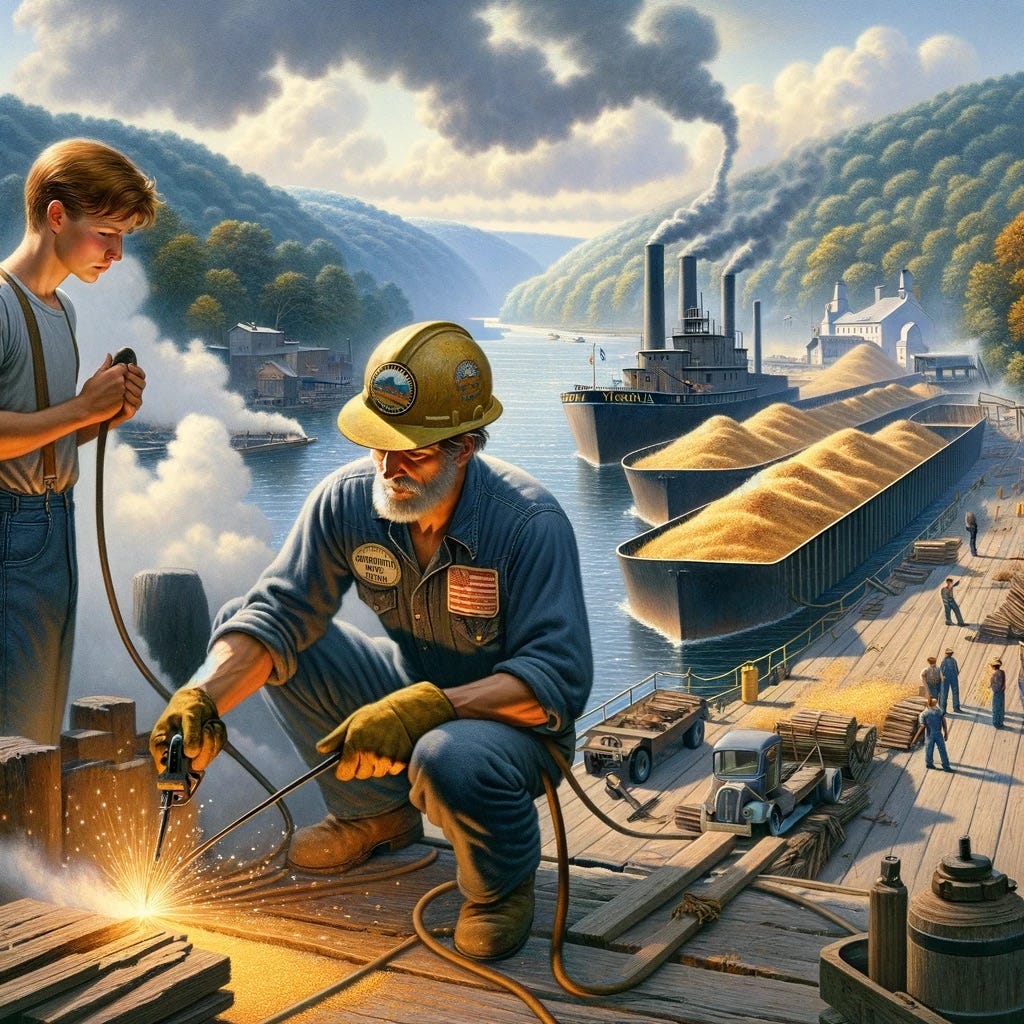

That day we had been tasked with replacing a length of chain on a chip transfer chute out by the docks. On the way, Big John had almost driven us into a forklift. I’d grabbed my heart and said “Jesus John! I thought we were ghosts there for a second.”

Having completely forgotten this context, given the length of time that had passed, and having a hard time understanding what he was even saying given the yodel, I simply responded:

“… what?”

John unfolded a remarkable and heroic tale from his own youth, right after he had graduated from high school some forty odd years ago. Back when he’d been my age, he’d gone to work in a logging camp in the middle of nowhere. Him and another young man made fast friends and bunked down together in one of a series of small cabins. Totally isolated from everyone, they slept there each night in tiny but separate rooms. That was when the ghost appeared. Infrequently, but always in the middle of the night, a dark specter hovered at the end of John’s bed, reached down and gently held his “honker” through a thin sheet.

Nineteen and full of myself, more concerned with being correct than kind, I asked a whole slew of follow up questions.

What was the roommate like? Did he go out much? Did the roommate have a girlfriend or a wife somewhere? Did he ever talk about women at all? Had John ever seen the roommate look at a woman with sexual desire? Had the ghost stopped appearing whenever the roommate was away?

As the answers unfolded to my expectations, I slowly led John to the conclusion that had been inevitable from the start. He had almost surely been sexually assaulted by his roommate. I let him know as much in a roundabout a way. I will never forget his response nor his manner.

“Nah, he was a Presbyterian.”

Entirely dismissed. My careful probing all undone. Big John had an air as if he had immediately solved a Rubik’s cube thrown at him randomly from out of a crowd, or stunned an audience of math professors with some irrefutable, cunning, and yet ultimately simple proof. There was no possible way to probe further. His defense was unassailable. Of course his roommate hadn’t sexually assaulted him because his roommate was a Presbyterian. A Presbyterian! You would have to be a complete fool not to see it. The only explanation that remained was supernatural.

Having delivered this killing blow, John returned to his work truck shaking his head and laughing at me for my ignorance. He drove off, leaving me to die a sort of intellectual death there by the river.

I stayed at the dock for another two hours as fire watch to make sure that John’s welds hadn’t left any smoldering sparks. There weren’t any. It was all blacktop out there with nothing to catch fire. So, I sat down and thought about John’s easy manner. His laughter at my statement, at my mere suggestion that a Presbyterian could possibly have done such a thing. His belief in the integrity of Presbyterians had been stronger than his belief in the integrity of natural law!

Later that day, in the lunchroom, I discovered that two other millwrights also claimed to have been molested by a ghost. One left the room immediately when the subject was raised, and the other refused to discuss it when questioned further. It was too painful for both men. And so it was that I ended that day having encountered my first bewildering and astonishingly strong belief in the supernatural from adults.

The sawmill was a bit of a story mill, too, you see. Lots of weird stories circling around from strange and irregular types of men like John. Odd stories. Incredible stories. Dangerous and hilarious stories. It was more than a summer job to me. More than a place, even. It was a rite of passage as sacred as any in the history of humanity. You couldn’t be a real, proper man unless you had spent some time in the timber industry. It was just known. My dad worked at the sawmill for something like thirty-five years, getting fired approximately every seven years for doing something like threatening to fight some panel of corporate big wigs during contract negotiations. He would then get hired back, via union protection, without ever losing his sense of indignity that some college boy pussy got him fired just because he threatened to kick his ass.

The mill was the spoke of a wheel. Everything of any significance that happened in our small town was something that happened at or in connection to the mill. If there were weddings or picnics or anything else, their cultural center and ultimate cause was that everyone worked in the same place turning timber into lumber.

A lot of what happened at the mill were horrific accidents.

Everyone at the mill had a story about almost dying. Lots of them had missing fingers to show off. Blood was the price and punishment for the crime of being thoughtless at the wrong time, if only for a few seconds. That’s all it took. A few seconds. Every man there made sure to tell us young guys that it could be over that quick. It was another rite of passage to have one of your fingers ripped off in some machine somewhere. Although, the longer you kept them all the more respect you accrued. When you eventually did lose a digit and came back from the hospital all the guys would sing the Mickey Mouse club theme song to celebrate your Mickey Mouse Hand. Three fingers and a thumb.

The whole culture was like that. Anti-Majestic is the name I’ve arrived at for it. Nothing could be anything except its most essential essence, the thing that it was at its barest and most minimum state. The thing that was revealed when you were under pressure and strain. Even your name wasn’t really your name. Your name was only a beginning bit of fodder for your eventual true nickname to reveal itself. Something to attach some larger eternal truth about your nature to the facts of your present circumstance.

Your nickname was given to you by the people you worked with to tell you something about yourself that you couldn’t change. To reveal your eternal truth, stripped of artifice. That’s how people like Bob Good Enough or Duncan Balls-Upon-Us were named when it became clear the former only wanted to do the bare minimum maintenance work to keep the mill running because he was lazy and the latter was both Greek and a micromanager. Big John, Little John, Little Jack, Big Richard, Dutch, Buck, Red-Eye, Nick at Night, a thousand other little names.

If Jesus Christ of Nazareth had ever worked at the sawmill his name would have been reduced to “Josh.” Sometimes people would probably call him “The Chris.” The Last Supper would have been called “The Last Lunch Break.” The crucifixion transformed into “That Time Josh got Nailed to a Joist.” The statue of David by Michelangelo would have become the statue of Dave by Mike Angelo. It was the complete opposite of the way you’d feel going to church where everything would be made bigger and more sacred. At the sawmill, what was sacred was only that which was supremely useful or couldn’t be destroyed even after deliberate effort. An aluminum pipe wrench was sacred. White Ox work gloves were sacred. A hot lunch was sacred. Your imaginary best friend was just bullshit.

I remember being blackmailed into going to church a few times when I was younger. It felt exploitative. It felt stupid. Against the anti-majestic grain of my culture. The only religious observation I had ever known was when my dad would do roofing jobs for free because, because and I quote, “I feel like I’m going to do something fucked up soon.” And a few times my grandmother took me to Sunday school at Our Savior’s Lutheran.

Who wanted to listen to some barely literate guy with probably a criminal record, given the community, standing up in a pew to yell at everyone? Not even compelling stuff, but stuff that you wouldn’t expect to see get more than single digit views on YouTube? Yet somehow it would hold an entire congregation in thrall. I only ever got suckered into it a few times. Enough to hear people talk about seeing angels and all sorts of other stuff. Stuff that immediately struck me as dishonest and theatrical. I distrusted the production around it most of all. The pageantry of it rankled me, like it was all a play and everyone was standing over a cliff and refusing to look down. All of them eager to help each other pretend and play make-believe.

I admired men like Christopher Hitchens, who strode like a lion even when he was literally just sitting in a chair on CNN, telling some college boy pussy that he was an idiot to believe in God. It made me laugh. It was vindication for every terrible thing that had ever happened to me in my entire life. Of course there was no God, because if there was a God, then other things would have to be allowed. Crazy things. Absurd things. Things like goodness and badness. Things like judgement and sin. I liked Hitchens because he talked with the attitude of the men at the sawmill, quick hurried bursts with no time for bullshit, except with an erudite British accent.

The guys in the lunch room got to talking about God one day in my second summer there. I was even more worldly than my first summer, having spent the previous year at college. You see, I was well on my way to becoming a college boy pussy as my father had always feared. I’d even landed a few prestigious scholarships, although they were somehow a mark of shame and embarrassment in my local community. NASA wasn’t supposed to give scholarships to people like me. Nobel Laureates weren’t supposed to care where people like me went to college. Being good at math or liking to read was something feminine, more suspect even than actual homosexuality. School was for environmental activists and mill superintendents who didn’t know what the fuck they were doing and wanted to put everyone out of work. So, I laughed at the lunch room conversation on religion, but stayed silent, and simply enjoyed and hated my aloof sense of superiority and alienation.

The reason for the conversation was that a millwright had come over from the small sawmill to the large in order to help us do some big maintenance project. He had been pronounced clinically dead some number of years previously after an accident. The story was that he had seen something in the long space between heart beats. He’d had a vision of another world in the few minutes he had been clinically dead. While the two buildings were very close, men working in one mill rarely had occasion to go to the other. The story was interesting and all the men wanted to hear it firsthand.

Buck, the man who had died, refused to elaborate. In a world in which nothing was sacred, he seemed suddenly as shy as a virgin in a brothel and the shyness of it was totally out of place. No man could work at the mill for as long as he had and be shy. Or, if shy, certainly not bashful. Not in a place where men would shit in your hard hat if they hated you, or squirt a tube of grease down your ass crack if you fell asleep on the job. No man could be too embarrassed to tell someone to shut the fuck up. Even I knew how to holler and tell a man to watch his fucking mouth when confronted and I was considered to be extremely suspect.

No one missed an opportunity to tell a story. Except, then and there, Buck didn’t want to say a word. You couldn’t drag it out of him.

“Come on! Did you see God and angels and the tunnel of light and all that shit? Did you go to heaven?”

Everyone insisted. Sometimes with vulgarity. There were jeers. Laughs. It didn’t feel like one of those weird church confessions where someone blubbered about seeing Jesus on a piece of toast or an Angel had helped them find their way in the forest. No poorly acted stage play about how everyone was really a friend to everyone else, deep down. It didn’t feel like a performance at all.

It felt like an interrogation.

When the yelling got to be too much, Buck simply sighed.

“Yeah, I saw all that fucking shit,” he said.

Simple. And when he said it the whole room went quiet. All that fucking shit. It should have been a joke. It wasn’t.

A man eating an egg salad sandwich, who was a machine operator on loan and looked a lot like an otter, recalled when he had been pronounced clinically dead.

“I didn’t see nothing like that. Just black and dark. I wasn’t even there. Went dark and came back. Nothing, forever.”

Buck nodded as if this made sense and one of the more vulgar members of the maintenance crew theorized this was because the man who looked like an otter was a piece of shit, to which even the man who looked like an otter had to nod in agreement. He was a piece of shit. Everyone knew that. It made sense. This did bring another round of laughter and with the laughter an end to the conversation.

And so the subject of the afterlife was left there, solved to the degree that any man there cared to solve it.

I would tell stories about it for years after. The way a near death experience had been summed up as “all that fucking shit.” It was so totally and completely absurd. Comical. The most supreme of all religiosity and the most profane mundanity pressed side by side, cheek by jowl. Majesty and Anti-Majesty. Cosmic Wonder and Common Profanity. All in a place where men claimed to have been molested by ghosts.

How could anyone believe something like that?

Except that years later, I saw all of that fucking shit, too.

Long years after the sawmill, I was twenty-seven and wanted to die. Even more cowardly, I wanted to die in a manner that could plausibly be viewed as an accident. Even to myself.

It was a strange cocktail of despair, bravado, and evasion. I rationalized that deniability was important so that my little brother and sister would receive the fifty-thousand dollar payout from my life insurance that would be otherwise voided by suicide and because an accident would be easier for them to process. The idea of something like a rope around my neck or a gun in my mouth also felt repulsive, common, and pathetic. I wanted something more elevated, bespoke, and furious and it would be years before I allowed myself the knowledge that all suicide is to some degree pathetic.

The cause of my despair was embarrassingly simple. Heartbreak. I had loved a woman who could never possibly love me back. She was unwell and could sometimes be cruel and I had loved her not in spite of her sickness or her cruelty but because of them. Now that I approach forty, I can see the obvious truth. I had been attempting to repeat the pattern of my childhood. Had latched onto the familiar contours of her personality, to the borderline personality disorder that gave me nostalgia for my boyhood, without consideration for wisdom. A story as old as time, and yet it was not all obvious to me.

For five months after her final rejection, I exercised vigorously to push away the pain and the shame of it. At least four hours a day, but sometimes five or six. Always at night or early morning. Always alone. Always vigorously. Anything not to think of her. Anything not to think, most painfully of all, of how she was almost certainly not thinking about me.

When I began, I was fat and out-of-shape. My sawmill body long ago eaten by a desk job and the hazards of corporate society. I hadn’t been able to do even a single push-up that first night. I’d cried like a child. Blubbering pathetic tears. I remember thinking things like “of course no one loves you, you can’t do a single push-up.” I had then done all the push-ups I could from my knees. I don’t remember how many but it wasn’t a lot. And it hurt.

At the end of that five months, I had lost a hundred pounds. I routinely did one-handed push-ups, or Spider-Man push-ups, or the ones where you clap behind your back. Push-ups in particular were very important to me. An act of aggression against what I perceived as the weakness of my past self. Most important was that I no longer recognized myself in the mirror. I was muscular and thinner than I had ever been. Handsome even.

I had done all sorts of other crazy things out of sheer annoyance with myself. Changed my handedness by wearing a woolen mitt I’d ordered off the internet for two weeks on my good right hand. I wrote equally well with either hand but always made sure to use the left. I began to part my hair to the other side. I paid for LASIKS so I didn’t have to wear glasses anymore. I went on dates and drank alcohol, something I had promised myself I would never do. I even briefly took up smoking. I’ll say this for the fat-acceptance movement, when I was thin everyone went out of their way to say hello to me and be kind to me. Women asked me on dates instead of the other way around, and by the way everyone responded to me, you would have thought I was doing extraordinarily well.

Except inside I was still the same. Annoyed by myself and all my various oddities and quirks. My absurd humor and melodramatic depressions. I have always strongly annoyed a certain kind of person, and now I was that kind of person. After five months, I knew that was no longer tolerable. Try as I might, I could not escape myself. And I was too tired to keep trying.

On the morning I ran by a canal it was spring. The water was high, cold, and fresh from the mountains. It flowed down at a steady current, but not so fast that it was fenced or in any other way guarded. I did my best to jump over it. It was at the very limits of my ability but I could clear the distance. Barely.

There it was. My plausible accident. A stupid man pushing himself farther than he ought. I wished instead that I could fight a lion. Or a dragon. Or anything big and terrifying so that I might leave the world in a fury. That was another reason I was ready to leave. Life was too mundane. Too boring. Too unheroic for my melodramatic sensibilities. If it were otherwise my tremendous efforts to change myself would have made her love me. My sweat, tears, and blood would have transmuted her nature. Instead, the best I had was the canal and I was not too proud to take it.

I figured that when I fell in and drowned they’d find my body at the next grate. My family would be notified and there would be no mystery. Not suicide but accidental drowning. People would say things like “he definitely should have been more careful.” The obituary might mention my potential, my scholarships, and omit the facts of my actual life trajectory, which were utterly pathetic. Apart from a mostly secret and unprofitable writing career, that I was also embarrassed by, I had nothing to show for my years on the Earth.

A broken heart is a banal, common thing. To everyone but the person whose heart is shattered, the way of mending of it is always an annoyingly apparent and stupidly simple process. As simple as lifting a cup of water and taking a sip. Go out. Meet someone new. Keep doing that. Simple. And it is always tedious to explain, for hours on end, to some tearful mewling kid that his arm really is strong enough to lift that cup and he won’t drown from that simple sip. Just go out and meet someone new. Keep trying. That’s it.

Maybe I knew that, even then, but I also knew that I did not want to try again. I only wanted the sanctity of my pain. I wanted my love to have meant something. I did not want a drink anew. I wanted something to matter above all other things. I wanted to lodge my complaint with the whole of the universe, to a God I did not then believe in, and the only way to make that happen was with my death. I had never loved anyone romantically before, never dared, had done my best never to have anything for myself —a punishment imposed on myself, by and to myself, for not having said something when I had been abused— and so to have the one thing I had ever truly wanted denied to me was the final insult. I did not care for the way this world conducted business, and had decided to leave.

So I jumped back and forth over the canal. I wanted to use up all of my newfound strength. I wanted to spend every last ounce of power that I had within me, so that I would be totally incapable of preserving myself when I fell into the water. It would be cleaner than suicide, I told myself. I would simply battle the universe until I eventually lost, as all men must do. I only wanted it to happen on my timeline. Not the same thing at all as suicide.

There was a small bank and elevation on each side of the canal. The distance was about ten feet. With a running start and the drop it was doable. Each time I’d have to scramble up the grade on the other side. Dangerous, yes, but doable. Five months previous I hadn’t been able to sprint for longer than a few seconds, so I was exhilarated when the water rushed below my feet.

My shoes rattled. I’d bought them when I was still fat. I’d shrunk so much that even my shoes were loose. That made me feel proud. I could feel mist coming off the canal water, slicking the hair on my shins.

I don’t recall how many jumps I made. I only remember the way my heart pounded. The way I sprinted and leapt and how my whole body felt sheer terror in the moment my feet left the ground. Then a few seconds later, the pure relief from that same terror. A feeling like “this is it, this is the time.” And then landing again, scrambling out, wanting to die in my mind but still so grateful in my body that each particular leap hadn’t been the one that took me.

My body knew it wanted to live even if my mind did not.

I felt totally spent when I prepared for what I knew had to be my last leap. There was no real chance I’d make it that time. Not with my legs on fire. Not with my thighs trembling. Not with my lungs sucking air. This time would be it. I was almost empty only enough strength left for a second of make-believe. I gave it all I had to give when I ran and jumped that time. I wanted to lose honestly. I wanted to be defeated by something greater than myself and so I gave all of myself into that leap.

I was much slower on takeoff than before. Much closer to the surface of the water. I knew that would be my doom. In that moment, I accepted the inevitability of my death. I would fall in and drown. No help for it. Every piece of me accepted death and if there is anything I suspect about my emotional state that may have been the cause of what happened after, I suspect that part most strongly. I stood before an open door, ready for whatever came next.

Seconds later, my knee hit the concrete slope on the other side. The foot of my other leg sunk partway in the water but only up to my knee. My hands instinctively reached up to grip the turf only a few feet over my head. I didn’t even slide once my grip took hold. Even though my every muscle was a wet noodle. Even though I was red-faced and sweating and wanted to pass out, I held fast.

I didn’t have the strength to pull myself up immediately. Still, I did not slip. I did not fall.

It took me the better part of five minutes to claw myself back up to the dirt walkway. I ambled along on two wet noodle-legs without destination, with barely anything resembling cognition. I was thirsty but had nothing to drink and didn’t care. I wanted to just lay down and pass out, but I kept on moving. I’d been ready to die before. I could stand to be thirsty and tired.

I had asked myself as honestly as I knew how and determined myself to be incapable of that leap. Then I had tried fully expecting failure. And I had won through, despite myself. I had no idea how to feel about that. It did not occur to me to simply throw myself in because I knew that was not what I had wanted.

I was, as I said, empty. And open.

After some period of time, my grandfather began to walk beside me. He was dressed like I always thought of him, wearing a blue-sweatshirt, khaki pants, and Georgia leather work boots. Silver-haired with thick-glasses. Like he had been dressed all those times he pulled me out of my dysfunctional home to go work on something productive at his house.

At that point, he had been dead for about eleven years. Liver cancer took him out when I was still in high school.

I was so tired that I didn’t care. Except maybe vague annoyance to be hallucinating. Didn’t give the smallest shit that a dead man was walking next to me or that my mind was breaking. Not even if it meant a dead man who had meant the most to me in all of my life was walking next to me. I wanted quiet. I wanted rest. I wanted finality. We walked together, silently.

It’s hard to describe what happened next.

Imagine you went into a dimly lit attic with holes in the roof. You pick up a handful of dust and blow it toward those cracks in the ceiling. Suddenly, the specific source of illumination is revealed and you can see clear and distinct shafts of light coming through the roof as if the light was something substantial you could pick up and move. The sun is still hidden, but you know it must be there to give source to the light. So it is with words, I think, and meaning. Words and meaning come to us from some sun we cannot otherwise see and whatever it is that we say or write is only a bit of dust that makes clear the path of its light.

There’s a line from a poem that comes to mind whenever I have tried to write down my experience, “The Net” by Sarah Teasdale.

It was as though I curved my hand

And dipped sea-water eagerly,

Only to find it lost the blue

Dark splendor of the sea.

Suppose you were the first person in your tribe to have ever seen an ocean. You could reach down and cup a bit of it in your hands to show the others, but it would not be blue. A description of it could not equal the experience of it. A piece could not come close to representing the whole. You might be able to make them understand there is a lot of water, somewhere, but not much beyond that. This problem is deeper.

It is hard to describe what I experienced next in words because what I experienced then is in some sense the only thing I have ever experienced. After this, when I read reports of religious experiences I became skeptical of words like “saw” or “heard.” Only one word has ever felt fit to purpose. “Revealed” as in “Revelation.” Like someone pulling a drape cloth off something to reveal its true shape, except the drape cloth was what I had previously understood to be the entirety of the material universe. Another description that seemed akin to my experience: “Seeing the light.”

One last word of apology, before we continue. I did not think of some of these comparisons until years after the fact. I did not leave this experience having immediately contextualized everything, and there’s much of it that I still question.

Here is the primary thing I realized as the years went on: We live our lives by experiencing the world through our senses, modeling the universe in our minds, and it is through that model and its feedback loops to our senses that everything we know as real comes to us. It is so fundamental to our condition that we almost never even spare it a thought. Yet what I experienced then, I experienced as myself, and only myself, directly. To borrow a phrase from philosophy “The Inscrutable Object” became suddenly not only “Scrutable” but the object’s “Scrutability” itself. The thing that I am, eternally, the pattern of my existence, touched the nature and patterns of other eternal things. It is not at all like what it is to live every day with hands or eyes or ears. The knowledge of other things was as immediate and intimate as “I think, therefore I am.” I know that doesn’t make sense and therein lies the problem. I can’t make it make more sense than that.

If you have ever read the Allegory of the Cave, it was as though my ropes were cut and I beheld, at last, what strange things there are that make the shadows on the wall. So, it is hard to use words to describe the experience because I believe that what I experienced then is where words and experience come from. I glimpsed the sun outside the attic.

My grandfather turned to me on that dirt path by the canal and though his expression was neutral I felt his concern. He was trying to speak to me but I couldn’t quite hear. I wasn’t close enough. I still wasn’t open enough. He had come to be with me from some other distant place in my hour of need but he could tell that his effort wasn’t sufficient. Something wasn’t working. He needed to do something to reach me and he needed help to make it happen. I felt something stretch from him —I don’t know how, I just felt it. Perhaps we can all feel the flexing muscles of ghosts and it is only that most of us have not had the opportunity to know it— out toward some other place I could not perceive. Something there answered his request as if it had taken his hand. Finally, whatever power he had beseeched took hold of me as well.

Things are about to get very weird and I apologize.

Reality… unfolded.

Causality opened up.

Those are not the right words, but they will have to serve. We move through three-dimensions of space. Height, depth, length. Those three dimensions, and others, unrolled all around me like a carpet, moving ninety degrees and ninety degrees and ninety degrees. Space and time evaporated, revealed to be illusions, a trick like when you view some picture from an specific angle and its two people kissing and then from another it’s only a vase. At some point I ceased to have a body and simply was, an indivisible being, a concept as essential as numbers. Although the shock of it was the most disorienting thing I have ever experienced in my entire life, it felt completely natural upon its completion. Like I was finally home, woken from a dream. The “real” world was the lesser reality, contained inside this higher one.

I stood on a mountainous beach with rocky crags that made a steep decline to a sandy shore before a vast ocean. Vaster than the universe, both the mountain and the ocean. But it was also not a mountainous beach. It was the idea of a mountainous beach. The concept of a place made of borders. Land, sea, sky. But it was none of those things either, except that place, which was not a place, contained their Is-ness.

I told you, it is hard to explain and I know I sound totally crazy.

I beheld a sun and stars but really they were something like “absoluteness” and “fundamental” or “I am.” That is also not correct but it is the handful of water I am able to carry to you from the ocean, apologizing all the while that it is no longer blue. The sun and stars not only shone with light but they did something like sing and the song was music itself, pure tones and vibration. Sometimes, I think I can remember the tune but above all the song was a word, a command to all of existence: “Be!”

There is no time there. Yet as soon as I heard the music of the stars, the sun became a figure standing at the exact point where the shore and the ocean met, but at the same time He was still the sun. Though He was a man with a human face I could not draw His face if you asked. It was the face of everyone who has ever lived, all stacked on top of each other, at the same time, like a mosaic. To look at Him was to see the depths of all those infinite lives. This was not horrifying but natural and proper, the way it is natural and proper when you step back from a smudge of paint to behold the masterpiece of a great painter. It was not the individual faces that were correct and of a piece, but their totality in Him that was most appropriate and well-ordered. His face, the one I had denied in my youth, I knew immediately.

He had been with me all my life.

Yes, sigh, I know it’s a meme. I know about the footprints on the beach. I know this makes some number of you roll your eyes.

And yet He is presence. He can’t not be with you. It was as if in seeing Him that I realized something I had always known but only temporarily forgotten. Something I had deliberately been made unable to see in order that I should be free to act as myself. In all of my memories, He had always been there, at each moment of my life, as though standing over my shoulder out of sight. And in seeing Him, with those memories restored, it was as if I saw my oldest and dearest friend, who knew me best and loved me most, finally reunited, at long last. I believe we will all see Him again, thusly, some day, the moment we meet our end and breathe our last breath.

There’s no time there, as I said, in that other place. The Platonic realm or whatever you want to call it. Heaven, if it doesn’t embarrass you. There can’t be time, because it’s the place where things like time come from. There is sequence there. Or the idea of sequence. The reality of sequence. The consequences of order. It is not the same thing as time.

I could see the whole of my life and still other lives that I had never lived. I can’t remember any of them now, but I knew that I could see all of them, if I chose. They were all pieces of me, a pattern running forward and backward across existence. I knew that was what I was, truly, a sort of fractal of repeating information, the same style of choice made again and again. To know, I had but to look, and I could flip through my every possible existence like the pages of a book.

I had always supposed the God of my youth was a man with great power, a superhero of profound ability, but in having Him revealed like this I knew that idea was silly. God is not Superman or a really big computer. You could not become like God anymore than you could become like gravity. If He has ever worn flesh and walked the Earth, it is only the extension of some small tendril of Him, something manifested to ease our understanding. I do not, by the way, claim to know if He has ever done such a thing.

I think other people have seen things like I saw, that it is relatively more common than we suppose, but throughout history some have made the error of assuming they took more back with them than they could ever possibly carry. Our human hands are too small to carry the ocean or even its true memory.

What I do remember is this, that in this highest reality, His bones are made of math, His blood is reason, His flesh is order. He simply is, apart and above. He is Is-ness itself. Timeless and Transcendent Moral Law. What Tolkien called the Flame Imperishable. The First Mover.

I knew I had to make it down to that strange beach, but really it was more like I had to find the point in the span of my entire possible existence where I was already at the beach, because I had always gone to the beach, have always been and still am right there in front of Him. I had only to sort of remember the point. I had to connect to the part of my infinite selves that knew how to move in the Platonic realm. Had to understand the connection between those things. In the Platonic realm, if we can call it that —or again, Heaven, if you are less self-conscious and less in need of apology— everything is made of ideas, of pure being, and we move through them based on our understanding of how they connect.

I think I remember that much. I think.

That’s the best way I can describe it, at least.

I understood myself to be on the beach before Him and so I was.

And I was full of rage. Or the piece of me back in Boise, Idaho was full of rage. That little puzzle piece of myself was furious. I threw all of that fury at him. Some part of myself extended toward His infinite existence as my grandfather had done in bringing me to this place. I felt an immediate right to such anger. As I said, He had always been with me. Is with me. Is with all of us. He is no stranger you might fear to approach. He had been there through every rotten thing that had ever happened or been done to me. I wanted to grab Him and to shake Him. And so, as I said, I touched Him.

What had He ever done? My mother was crazy and I had spent almost my whole life trying to clean up her absolute disasters. She had invited a crazy man into our home when I had only been a child and the things he had done had been horrific! My father was an idiot and constantly needed to be pulled out of some mess of his own making. I had a little brother and sister that I had been as dutiful toward as a son and a daughter, and it had been so painful to take on that responsibility as a kid myself. The ugliest night of my life when I had set out to kill my step-father because he had tried to murder my mother, what had He done? I had only been a boy. The rape I suffered as a child, the responsibility and burden I felt, the coward way I couldn’t even apologize to my cousin for not speaking up. All of the terribleness of the whole world, what He done for any of it? What had He done?

It is so hard to explain the feelings I felt because I did not feel them as a person with two hands, two feet, and two eyes. I saw more like Tralfamadorian in a Kurt Vonnegut story, perceiving all of time as one burning instance. I am all the moments I have ever lived. All the moments I will ever live. All the moments I could have ever lived. We have arguments about the nature of the self, but in that place beyond space and time the nature of the self was obvious. I am all the moments of myself that I recognize, that I can wrap my mind around and know as part of a greater whole. All those moments scattered across space and time like the pieces of a giant puzzle.

In touching me, He brought those discordant pieces into a sudden order and I saw myself as He saw me. I saw the picture that emerged from the puzzle pieces.

I was strong, then. Fearless. Full of knowledge. Expanded so that when He spoke I might understand Him.

The sun grew, filled the whole of everything, and though the knowledge left me as soon as it came, I understood how the infinity of Him had become the finite world in which I lived. I understood why He had ordered the world as He had and why it was Good. —Again, I no longer remember any of this, I only have the memory that I once knew. My comprehension was bigger, there— The sun was not only the sun of the Platonic realm, the command to Be, but also the regular glowing sphere of gas sun over regular old Boise, Idaho. The two places were always the same place, each laying on top of one another. Always there, always accessible, for if they were not we would not even be able to think and there would be nothing to think about.

To be as I was there, in the World Above, was as incomplete as to be only in the world I had always understood to be the only reality.

And, yes, I felt His love. Unfailing, endless, impossible love. I could write out whole books on the nature of His love. Under it all, beneath everything else, He is made of love. It is the ultimate substance of Him. And I hate that I even have to use words to describe it that way, or that it sounds like something some drug addict might say to describe an LSD trip. Or some guru at a retreat somewhere who is happy to tell you more but first off, they really need a lot of money. I could spend endless pages describing it and this is the most frustrating piece of the experience because neither my throat nor my fingers are a wide enough channel to describe it to you nor can they ever be.

Whoever you are, whatever you have done, He loves and accepts you.

I can tell you that for the first time in my conscious memory I was at peace.

He spoke three words in answer to my question. What had He ever done?

I sent you.

The words came with His understanding and I suppose that is what all words are in some sense, pieces of His understanding. What He had done for the disorder of the world was to create us. He had done this for everyone, not only me. He caused us to be. He upheld existence. He had made us as we are so that we could find within ourselves the capacity to face challenges, to overcome hardships, to be brave. His greatest gift was to us was the one thing he lacked. Our limitation. Greatest of all gifts, so that we could win through risk and fear to find love, truth, and beauty and own the things we won. So that we might, in our inherently uncertain world, figure out who we really are. For in that way, by overcoming without knowledge of the outcome, by risking without certainty of reward, we could become most like Him.

I understood.

I had failed so many times in my life. Betrayed my own nature and spit on His name. But I had not always failed. I had succeeded, too. I had been there to help my little brother get through school when he had struggled. I had been there to protect my little sister when her father got out of control. I had kept my mother and father going, for a while anyway. And because He did not intervene, because He had only ever stood over my shoulder and watched the moments of my life beyond my line of sight, those successes were mine in a way they might not otherwise be. The part of my identity that chose to do them was mine. And my failures could be forgiven because I was not as infinite as He.

For all of my life previously, as I said, I had supposed if there was a God, that he must be some flesh and blood scientific-wizard who could pull the levers on a vast machine to arrange matter however he wanted. But God in the highest sense is moral law itself, its substance, not even so removed as to be merely called its author. Give a man control of all the atoms in the universe, all the energy as well, and let him arrange them however he wills, and even if he tried forever he could not find a single pattern out all those possible patterns that could transmute injustice into righteousness or cold cruelty into friendship. I am that I am He had said to Moses. And I understood it then as I had never understood it in the few Sunday school classes my grandmother took me to in the church basement. Moans and whines about God having done this or having chosen that were nonsensical. As are complaints that religion and science are at odds. He is. He is all that is. Eternal and beyond time. If He intervened, day to day, if He had set up the world otherwise, none of us would exist. We would not even be an “us” only an extension of Him. All of reality as we knew it would break.

I felt full. Complete. I was no longer thirsty.

Yeah, yeah. Living water, or whatever.

No sooner did I feel that completeness then all of eternity tucked and folded like origami back upon itself. Pure being became physical reality in some manner I do not and will never understand while I am alive. This time it felt like falling from an impossible height. My whole body jolted when I realized I was no longer on the shore of a beach before God, but for a few seconds I stared at the sun and could still hear the music of heaven singing “Be!” Then it was silent again and I had to take my eyes away when they burned from the physical, normal light.

I no longer wanted to die. No longer felt crazy with despair. In fact, I felt saner than I had ever felt in my life. I hurt, but it was a containable hurt.

And I did what any of you would do if something like that happened to you.

I booked an appointment with a therapist immediately.

This is my version of telling a ridiculous and unbelievable story about being molested by a ghost that immediately causes people to suspect other explanations. I know that. There is no help for it.

I do not particularly like to tell this story. I know it sounds, to steal a phrase from the British, “absolutely mental.” Maybe it is. It’s fodder for people to immediately create entirely materialist explanations and say things like “that bit about falling at the end, if you have a seizure in such and such an area of the brain it causes such and such a feeling.” Maybe you’re right. He is inscrutable on this side, after all. Are there seizures that induce feelings of Platonism? Maybe. Perhaps there’s some evolutionary explanation for why people have near death experiences or why people at high altitudes hear voices or sense a presence trying to help them get back to safety. Maybe in a moment of high emotion my brain triggered some kind of hard reboot like insanity. In my understanding these things are mutually compatible with the divine.

Suppose you went into the attic described above and blew that same handful of dust. The shape of the light is all but unchanging even as the particles are constantly moving in and out, to all be replaced in time. In such a paradigm, which thing is more real? The dust or the light?

I can’t deny the experience. But I do not deny mathematical identities or evolution or anything like that. Rather, I think they are something like His thumbprint, an impression of His higher order, left behind in the clay that formed us.

It didn’t feel like I was falling at the end. I’m using words to map to something else. It was falling. It was the idea of falling. The Is-ness of falling. The only thing that surprises me is that I’m somehow able to remember it.

I know this is not evidence in any rigorous sense because it is not replicable. And I also know it can’t mean anything to anyone in a rigorous sense outside of myself because, hey, I could also just be making it up.

If you’re particularly prone to believing me:

No, I don’t know if Jesus was the son of God or if Mohammed is his prophet. No opinions in particular about Buddhism other than that the West seems to fetishize it a bit. I don’t know if some religion has it more right than some other religion and God didn’t also secretly tell me that I should get to have sex with everyone else’s wife or start a cult. I also don’t think I’m particularly special or chosen or anything like that.

I think things like this happen relatively more often than you would think, like coming across a bear roaming around a downtown area somewhere in Alaska. It happens. It’s discordant with other things that normally happen but you’ve seen news reports about it. It still surprises you even though you know that there are reports that bears sometimes do this. It just happens. Sometimes you walk downtown to go to your favorite coffee shop and a bear is wandering around. Sometimes people see God.

If He is always with us, and cares about us deeply, I think sometimes He can’t help but tap on the glass as if to say “Please, just stop and think for a moment. Please. It’s very difficult to be an eternal being outside of time and space just watching you make the same mistakes over and over again.”

I did start to look at religious texts differently after this happened. Less total dismissal of random events and more of a reading like people doing their earnest best to try to document and preserve instances of what I call “Cosmic Horseshit” and figure out what they mean.

For a long while after this, I denied the reality of my experience. I figured if I spent long enough in therapy that I would figure it all out and I’d be able to dismiss entirely the discordant reality that something like “God Himself” had finally shown up to answer my junior high school challenges that He appear and prove His existence to me. If I just talked to someone long enough it would all become a safe delusion, and I’d just need to take a pill or something. I spent years moving in this general direction.

Rationalizing it away was easy. I spend a lot of time in my head. I spend a lot of time crawling around in my imagination. I can dream up whole stories, or worlds, or whatever that don’t exist. Surely, I could have just imagined the whole thing. And yet nothing has ever felt more real to me in my life, except maybe once.

To what I suppose are your other questions: it does feel weird now when I do all the kinds of rude things you’re thinking. I try not to think about it. Also if you’re gay or whatever, I think He only really cares that you try your best to do what you think is right, and to be honest with yourself about really doing good things. He didn’t tell me that but it was, as the kids say, a strong vibe. We are beautifully, terribly finite. Limited, that we might grow to become ourselves.

I do also admit to some smugness when I hear Sam Harris —who I confess I find just generally annoying— talk about doing LSD and seeing a panther. If you’re going to have a hallucination, even if you think it’s only a hallucination, at least have a big one. You can see a panther on television. I also admit trepidation that anyone takes psychedelics at all. Those reports sound quite a bit like what I saw except for one major difference: the “beings” encountered while on such trips are frequently reported to say that life is just a joke or a game and then encourage the drug-taker not to treat life so seriously. That is the diametric opposite of my own experience, and if what we are, we are forever, I understand where the Biblical admonitions against sin come from. Yet at the same time, we can only be ourselves.

It wasn’t like I felt perfectly great afterward. That feeling I’d had in what I now think of as the Platonic realm —or, again, Heaven if you are less bashful— of being a perfectly ordered being went away almost immediately. What didn’t leave was a sense of internal connectedness. Like I’d been a puzzle whose pieces were moved into a greater order. The perfect order was gone but enough had stayed clumped up together that I could at least get a general idea of what the whole picture was supposed to look like. It was also like a wide open wound, long ignored, was now screaming at me that it be tended.

Therapy really did help me get my life back together. So I kept moving in that direction. I talked about all the things I used to talk about as jokes, like about how my mom once took off with my little brother and sister to Disneyland and then called me and demanded I give her all my college money because she couldn’t afford to get passes and didn’t have any money to get back, as the deeply hurtful betrayals they were. And I faced my resentments and made my peace with them. I had a good therapist that didn’t let me stew in things, or indulge in bitterness, and if I said something like that I was afraid of crowds she gave very practical advice like “go sit in a crowd. It’s fine.” Small things, small changes, that became bigger over time.

One day my therapist gave me a flier for group sessions run at a local Baptist church for people who had been sexually abused as children. Once per week and it was free.

I have never been so terrified to go to a place in my entire life. I’d have rather walked into a mafia den or one of those prisons in the wilderness where they keep members of MS-13. There were all kinds of reasons I listed out for why I shouldn’t have to go. Looking around, I also realized that my best judgement didn’t seem like it had landed me in the best of circumstances. So I went even though I didn’t want to go.

The first two things I noticed upon entering the room was that the facilitator, a man named Dave, was about a hundred years old and anytime someone spoke he had to turn toward them and hold his hand around his ear to help him catch the sound and also that every single person had moved their chair so that they could be facing the entrance. I can’t talk about the actual sessions much since I took an oath of ultimate double top secret secrecy. I will say that there were times I didn’t want to leave my truck to go inside, but that every time I left a session I felt like the weight on my shoulders was a little bit less. There’s a peace in knowing you are not alone even if you don’t think there is.

I bring it up only to say that I suppose there are different kinds of love, and when I asked Dave why he did what he did and for no money —because I could see how much it hurt him to be there— he said he did it for Jesus. That still makes me choke up, just writing it. He said it with his whole body, his manner, and all the history of his life behind it. He was the first real Christian I had ever allowed myself to know. It wasn’t a stupid person’s answer and I don’t particularly care if anyone anywhere has ever made quite a lot of bread and fish appear in a place that didn’t have a lot of bread and fish before. I don’t think you’ve lived a foolish life if you’ve decided to care deeply about other people and try to help them for any reason. So maybe this is me sneaking in here that of all the religious traditions I do think Christianity has it “the most correct.”

I don’t think you could ever uncover something that said a man died while nailed to a cross and that actually nothing else happened afterward and then honestly infer, “Hold on, someone snuck out the body. Time for us all to stop being kind to each other, then. I feel like such an idiot for helping all those poor people when the guy who told me to do it didn’t even have magical powers.”

It’s so easy to smirk and say “Do you really believe He turned water into wine?” And so impossible to say, in earnest, “Do you really believe we should care about everyone, even our enemies?”

The greatest proof in my mind that Jesus spoke something like the truth is that it’s very difficult to take the bits he actually said and make them funny. All of this is to say, it was the first time after my experience by the canal that I felt something like the love I had felt in that other place. It came from Dave.

I felt that love again again when I met my wife.

Still, I held back. Delusion. Temporary delusion. That’s all it was. A hallucination. It’s nice that we can love each other but there are secular reasons for it. Chemical tugs. That’s all they are. Evolutionary imperatives. Just follow them along, it’s what you were born to do, after all, but certainly don’t believe there’s any greater purpose in that. That would be crazy.

I felt that love again most strongly when I held my son for the first time. The only thing in real life that was as real as the reality of that other place. It was like I held a point in a line that ran all the way back to the moment of creation and all the way to the end of time. I did not care to look in either direction because that one solitary point was the most precious thing in the universe. In holding him, I held everything and loved everything for making him possible. It was undeniable then. There is a love so vast and so powerful that it transcends time and space, and binds together everything that is, was, or ever will be. It is the love of a parent for a child. His love for us and His gift to us that we might come here for a little while and know one another.

We saw a sonogram of baby number two yesterday. I felt that same love, yet again, and I suppose that’s why I’m finally pushing publish on this piece.

So, there it is, honestly recorded even if it is all a bit insane.

All of this is to say that if a man named Big John from West Virginia ever yodels at you that he was molested by a ghost… I mean, he probably wasn’t and there’s a much more tragic but rational explanation. But maybe?

Because Nadia Bolz Weber said to read this, I did. Good advice!

You got me crying ❤️

Damn. I'm an atheist and this piece just blew me away. It deserves to be read.