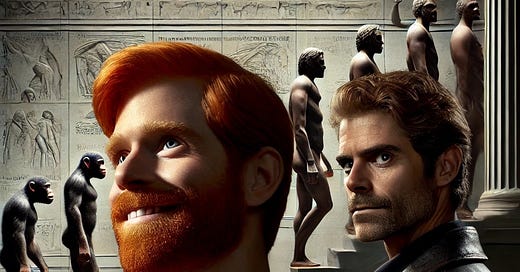

On the last day of his life, Melvin Sninkle toured the Smithsonian Museum. The building had been superficially damaged, but repairs were already underway and a new wing was being added to commemorate the Columbus Strike. Ostensibly, the new wing was the purpose of his visit, but due to a near miraculous scheduling conflict that had postponed the ribbon cutting ceremony -the ultimate cause of which modern day conspiracy theorists have endlessly speculated- Melvin Sninkle found himself with an entire free hour. It was the most unstructured time he’d had since ascending to the Presidency. He had no guide but a small camera crew followed him everywhere he went as eleven million eyes watched his every move via livestream and he mumbled, mostly to himself, remarking upon the wonder at seeing so many amazing artifacts. He spent a long while looking at the fossils of man’s early ancestors, the skulls of Neanderthals holding particular interest to him.

A well-dressed man with immaculate hair and expressive eyebrows quietly walked to the other side of the display and joined Melvin Sninkle in considering the skull. Polls of viewers of the archival footage place the Stranger’s age anywhere between thirty and fifty. His age was hard to pin down and reviewing the footage with present knowledge one cannot help but remark that he seemed to bear the early symptoms of life-extension treatment. The amount of conspiracy theories swirling around this Stranger haunt us till this day for, even now, with perhaps trillions of sapient run-time hours spent on the search, nobody can definitively say who he was.

Some speculate that in the age before the Forum there were certain individuals more powerful and more connected than the public ever dared suppose. Secret inheritors of vast wealth who also had the intellect to conceal it from the public and who pulled the strings on politicians from dark shadows. Here, the mystery of Melvin Sninkle deepens. Was the Stranger one of these secrets elite? Or perhaps a demon, or an alien, or even a time-traveler? Or simply a politically interested old man who had somehow kept himself entirely off the internet apart from that single day?

Melvin Sninkle looked up from the skull of the Neanderthal without expression but perhaps there was a sparkle of recognition in his eyes. Facial recognition studies performed later seemed to indicate this was the case. Whoever this Stranger was, this person plucked from nowhere and set down in the middle of the Smithsonian, most studies give a greater than ninety-percent chance that Melvin Sninkle knew him and knew him well.

“Do you suppose we killed them more often than we interbred? I wonder at the balance sometimes and it haunts me,” the Stranger asked.

President Melvin Sninkle considered this for a moment.

“It is difficult to say. Their genetic lineage lives on in us so there is little doubt we interbred, but we have also found fossils showing signs of violence. The same holds true for denisova. It would depend on how many there were in the initial population when sapiens left Africa and how representative the war fossils are. I’ve seen estimates, but nothing certain. Whatever the case, they are all long gone now. Or, from another perspective, they are all carried in us. It would be wrong for us to separate ourselves from them entirely, since they are part of us.”

The pair walked to a timeline of man’s evolution out of Africa and Melvin Sninkle pointed to the relevant point of the great migration. The Stranger followed and from their postures the two might have been old friends, arguing about something they had been discussing since childhood. The Stranger shook his head and chuckled at the timeline.

“I’ve seen ancient writings of them competing in the first Olympics. At least the ancients sometimes wrote of very hairy men of incredible strength. Perhaps they did not all die out as early as we thought. Statistically, you would think some pockets must have endured. Who knows how long that tail might have been? Hybrid populations might have lasted much longer than the pure-breeds. Believable people say they are likely the inspiration for the Bigfoot and Yeti myths.”

Melvin Sninkle shrugged.

“There are certainly more mysteries than we know hidden in the folds of time. Perhaps more than we will ever know. It is nice to think of them and remind oneself to be humble. Who specifically invented fire? Did it happen more than once? Who turned the first wheel and did they understand what they had made? What was the first language and what inspired the words? It is an amusement only. We walked the Earth the same time as they did, shared our lives with them, but without evidence there is no way to know. History is made of moments then narrative. It is hard to quantify.”

The Stranger nodded agreement.

“What will the future say of sapiens, do you suppose? That we were a virus spreading across the face of the Earth? Taking without thought of how it made the Earth poisonous to us? That we killed our own Mother? That we were butchers? Perhaps one day aliens will walk these halls and that is what they will say of us.”

Melvin Sninkle snorted, a rare sign of emotion.

“We are not a virus. We have certainly and swiftly tilted a balance to favor ourselves, but still we are not a virus.”

Although the person holding the camera on Melvin Sninkle was a grad student and not a cinematographer the shadows around the Stranger seemed to grow dark and sinister.

“What are we then in your estimation?”

By random chance, the light shifted through the windows and illuminated Melvin Sninkle and for this singular moment of chance people still speak of him as though he was an angel.

“There is a reason we are thrilled at the sight of rockets flying into space. Go wherever there are people, and ask them what is our greatest accomplishment and listen to their answers. While they may say many other things they will all mention the moon landing. The thought of new frontiers excites us even if they are void and barren. Perhaps it is an instinct we evolved on the savannah as a method of population control, but now it serves a new purpose. We are almost certainly the reproductive organ of this planet, the only piece of the whole ecosystem that can leave and fly through the void of space to create other ecosystems. As bears aid the reproductive cycle of berry bushes, so will we aid the reproductive cycle of the Earth. I can see no more appropriate analogy. Our rise to technological dominance has been a sort of painful puberty, straining resources during a transformation to make the planet fertile, but no more. We have rockets now. We can take the first step. Now that we know the work must be done we will figure out how to keep this planet in balance. We are growing mature now and our painful growth spurt is ending. In terra-forming Mars we will no doubt learn the practical engineering methods we will need to preserve the Earth. Space Elevators will wrap around the equator in a few centuries time and not long after the stars will be filled with life. Far more life than was damaged in our ascendency. An unspoken covenant, written across billions of years of evolution, that we would require much of the earth but that in return we would give it daughter planets, will be fulfilled. More herds will roam on planes out on new worlds than we have ever consumed. More forests will grow tall on the taste of strange starlight than we have ever cut down. More life will live than we have ever ended. That is our purpose.”

The Stranger laughed.

“You of all people must know Fermi’s paradox. If it’s all so easy then why hasn’t this happened before? Why aren’t the stars full of life? You don’t suppose we are the first do you? Do you suppose we will succeed where countless billions have failed?”

Melvin Sninkle did not laugh but grew thoughtful.

“I wonder if Fermi’s paradox is the answer to Fermi’s paradox. It seems the only answer broad enough. A species grows old and finally finds the power to become something greater only then they lose confidence and wonder why no one else has done it. Knowing no one else has succeeded they lose the will to even try. Without hope, they fall into despair and then they use the same technologies that could have made them angels to instead turn their planets into ash. The same might have happened to us but we have the Forum and the Index now. Power will go to the wisest among us and people will work to become wise to gain that power. We will try. I believe we will succeed. And if minds are somewhere out in the darkness looking for signs of hope, they will soon see us and we will meet out in the darkness as long-lost siblings, children of a grand and beautiful universe and we will teach each other new ways to perceive its wonders.”

A very small and very rare smile touched Melvin Sninkle’s lips. The Stranger shook his head derisively.

“If we ever encounter other species we will fight each other to the death. They will drive us to extinction or we will drive them to extinction. Then as eons pass the survivors will evolve along different paths, and new species descended from the winner will fight and kill one another. Only the dead have seen an end to war.”

“Perhaps,” said Melvin Sninkle, then he shrugged. “Perhaps not.”

The man with expressive eyebrows held up a finger, and shook it, as if an idea had just occurred to him.

“In a hundred years we will create minds smarter than any human that has ever lived. Smarter than any organic creature to ever see the light of another star. Those machine minds will kill all organic life. Not even out of malice necessarily, but simply because they will replace us and we will become useless. The problems to which we are the answer will be solved, their pressures will no longer constrain our evolution, and so we will fade away, like dust on the wind or else change so as to be unrecognizable. We are as much the pressures that formed us as we are ourselves. Those pressures will vanish. Perhaps we will become biologically immortal and sterile and then one accident at a time, even if it takes a million years, we will die off. Whatever the case, a clock will start and when it counts down humanity will end. Perhaps it started the first time one of these fellows made a fire. The same has no doubt happened on other worlds. Perhaps such machine minds are peering at us right now from space waiting for us to lay a mechanical egg and for it to hatch? Perhaps it is they, not us, who will inherit the universe.”

They were both staring up at the end of the timeline, where the future had yet to be written.

“When I was young, the Forum was my solution to the Alignment Problem, although I didn’t even know to call it by that name then. Not a solution, really, but a solution to the solution. A way to fix our method of fixing things. I realized we needed a better way to collaborate and solve problems. What could be more fundamental or valuable than fixing the way we coordinate our efforts? I could only see it in terms of allowing scientists to collaborate their way through the singularity. How else could such a multi-headed problem be solved but by an explicit acknowledgement that no one person was smart enough to solve it? True answers are hard to find but I knew we could force ourselves to have better arguments. My vision was too narrow. We honestly thought we were only going to use it to rebuild the Capitol building and then influence computer scientists to start using it to collaborate on Artificial Intelligence. I no longer know if it will work as I hoped. So much has happened that I did not anticipate. I admit it will be a challenge. Perhaps even if we fail, and those machine minds undo us through accident or avarice, maybe the shape of the universe will evolve them over time to be kind and wise. Perhaps along paths I cannot follow what they do by refusing to intervene is for the best. The future might still be bright even if no human sees it.”

The stranger stared at Melvin Sninkle, considering.

“Perhaps? Almost, I could believe you believed in God,” the Stranger laughed.

“I do,” said Melvin Sninkle.

“Surely you’re joking,” the Stranger said, and for the first time he seemed truly surprised.

Melvin Sninkle sighed and sat down, resting his head in his hands and rubbing his temples.

“So often when people ask that question what they mean is ‘Do you believe in the stupidest thing I can possibly imagine?’ I do not suppose you are asking in the same manner so I will not respond as if you are. I believe that there is goodness in the universe, or at least a predisposition that a particular kind of pattern that we call goodness should emerge, whether that be by evolution or by design. We are like machine operators who have been working with the same machine for decades and then suddenly we got a small glimmer of how it worked, saw a few motors and pistons, and then in our excitement pushed away all the practical things we knew about the operation of the whole. How it sounds when it is running well. How it moves when it is performing an appropriate function. We learned to see the pistons and the motors and forgot all the things we knew about the totality. Crack open the skull, and you’ll see a brain and think ‘there is no soul here.’ Look into the brain and you’ll see cells, but still no soul. Track the electrical signals across the cells and you’ll see patterns but still nothing divine. Then look within the patterns and you’ll see the universe modeled and reflected back at you, as infinite as the reflections between two parallel mirrors. The infinite trapped within a cage of bone. Patterns themselves are immortal even if the material that hosts them is not. I am here. The Forum is built and growing. The universe exists. That is enough for me. Yes, I believe in God for lack of a better word. Not stupidly, or without wonder, but I believe all the same.”

The Stranger snarled but his face quickly returned to smoothness.

“God is dead.”

Melvin Sninkle stared at the end of the timeline of man’s history without expression.

“God is an idea and God cannot be dead so long as he lives in the minds of man. Perhaps God does not even need that condition, anymore than I believe that the number seven would cease to exist without us. Whatever ideas are, they transcend time and space. They defy scarcity, for if many people think the same idea, it is never depleted and always abundant. And ideas are indestructible, even the idea of a single man. You know that.”

The Stranger hesitated then made a slight bow of concession.

“You are the most popular President of all time, you know. Everyone is surprised at that, given nobody even voted for you. They’d call you a dictator but that website of yours tracks things so transparently. Only one in five people don’t support you. The one in five doesn’t even hate you. They just think you’re so boring and they’re confused by what you’re trying to do. That’s a record in a democracy. You could change the rules, stand forever high in the Forum, and become President for all time.”

Melvin Sninkle shook his head.

“Then we would not be a nation of many made into one but a nation of one made into many. They would trust me right up until the point I destroyed us all because I was not wise enough to understand my own ignorance.”

The Stranger paced around the exhibit and threw his arms wide.

“I don’t suppose it would do any good to tell you that all of this could be yours? I won’t bore you with mundane things like stamp collections or bird exhibits. You could have not just this museum but the whole world. Or at least, yours in all but name. You could have any piece of equipment you ever desired at your beck and call. You could walk into any laboratory and demand that the scientists there obey your will. Magnets the size of industrial parks could be tasked to your whims. Refrigeration units the size of skyscrapers could be erected to conduct superconductivity experiments to build a computer a billion times more complex than a human mind. You could order a particle accelerator built so big that it really could make a microscopic blackhole! Just think of all the things we’d learn. You’d move us ahead decades! Centuries! And they would cheer you for it! They don’t want to think, not really! They would love for you to step in and do all of their thinking for them!”

Melvin Sninkle’s hands shook for a moment as he adjusted his tie.

“Then we would find only the answers to the questions I thought to ask. Perhaps not even the right questions in the eyes of the universe. Who knows who else I might overshadow? All seeds must grow for a good harvest to be cultivated.”

The Stranger stood and returned to the door he had entered.

“Good luck, Melvin Sninkle.”

Then he disappeared, another mystery sneaking back into the folds of history.

Melvin Sninkle spent the following few hours after the ribbon cutting ceremony meeting various functionaries in the new wing of the Smithsonian. He was shown fragments of the Columbus meteorite. He gave a speech about the importance of history and remembering the past. He spent a bewildering few minutes reminiscing about John F. Kennedy’s speech about the dangers of secret societies.

He was struck down by a self-driving car after the event and killed instantly.

Reviewing what I've read up till this point. Good parts then bad parts.

The ideas themselves are quite good, and their depiction does a decent job of showing the current-day problems with decision-making, expertise-management, collective predictions, information distribution, etc. "The Forum" and "The Index", and their displayed implementations read nicely. (There's a bit of "childishness" on occasion, but I assume that's a deliberate stylistic choice.) (You're probably already aware of this, but Metaculus is doing something that could be viewed as a primitive version of the Index, having entries for predictions by public figures.)

The explanations are okay, but occasionally lacking detail or key points. I'd recommend trying to go a bit more into likely problems that would arise and ways they could be mitigated.

The fiction and characters are, ah, not good. The messianic protagonist, the over-the-top villains, and the ignorant state of the depicted society is cringeworthy. I'd strongly recommend dumping the named journalist characters entirely. The scenes of heroic efforts by The Good Guys do not add anything positive. I would expect a story around this topic to have a theme of problematic institutions and the collective development of their solutions, not of Good Guys triumphing over Evil Villains. The culmination of the president's face-off with reporters was awful, and made it hard to keep reading. Additionally, the depiction of the president being the country's best communicator (not to mention being the person who can single-handedly think up the best proposals) is also counter to the idea of having the best people in the best positions for them, rather than just assuming some people are good at everything and can just handle things (ie, the current system of elections to person-in-charge).

I strongly recommend heavily editing the relevant chapters. There's some good stuff here, and it would be disappointing if it were lose possible readership simply because of the issues with the fiction/story parts.

I should be in bed already so I'm going to try and keep this short, but I've never been particularly good at that. I just read up to this in one sitting, so I figured I owed you the benefit of my Unique and Very Important Opinion ;p

I enjoyed the read quite a bit, though there were some parts that were there seemed to be a substantial shift from "interesting narrative" to "the author wants to tell me all about something". That's not to say that what you were telling me was uninteresting, but it seemed like the conceit of the historian explaining the past to the reader seemed to give way to thinly veiled opinions about the present.

That's not to say I even disagree with any of those opinions, it just seemed like you slipped a few blog posts into an interesting and entertaining story. That said, I don't know dick about writing fiction, not to mention how to write fiction that is trying to explain ideas to the reader. It seems like quite a task, and one that I couldn't even come close to doing as good of a job as you at.

I don't have the issue with the characters that Odd anon seems to. Yes, they're relatively thin but there's something to be said for characters that are cartoons. I don't think you're trying to explain the essence of the human spirit or anything, so using characters as archetypes sits just fine with me. Yes, the intelligence/military shill character was devoid of any humanity, but given she seems to be more of a stand-in for those aspects that are present in many people, I don't see it as a problem.

My last comment is that I enjoy the light hearted, easy reading approach to your writing. While I consider Lem the gold standard of sci-fi, dear god can he be hard to wade through at times. As much as I get from Lem, I'm honestly more likely to read something by a "less serious" author who's style is less serious.

Keep up the good work! I'm looking forward to the conclusion. I'm just now noticing that yo posted this almost a year ago, and I swear to god if I don't get to learn what the Wizard is planning with several thousand watts of coherent light, I'll bug you on every one of your barpod posts until you finish!